There is one particular reason why my study of economics is very interesting: I am confronted, repeatedly, with traditional economic models, theories, and arguments. Some of them are of some value, many are not (maybe for training some basic economic understanding, but not for analysis of real world problems). Recently I attended a lecture in Advanced International Economics, in which the theory of international trade by David Ricardo was presented. For non-economists: Ricardo developed the first major theory of international trade (in the beginning of the 19th century). It is a very simple theory built upon the foundation of the so-called “comparative advantage”, stating that trade between two countries is mutually beneficial when their relative productivities are differ (not as in Adam Smith’s theory, where only absolute productivity was of meaning). For a short introduction see here.

After having explained the theory, the teacher wanted to show us how it can be applied to real world problems (though he himself had pointed out to some deficiencies due to basic assumptions of the theory): he picked up some “frequent antiglobalist arguments” against free trade and “defeated” them using Ricardo’s simple comparative-advantage model.

The arguments are very simple: free trade is bad for developing/poor countries, especially because the richer countries are much more powerful. Multinationals from the developed world are exploiting workers in poor countries.

First, my teacher have shown, using the basic model by Ricardo, that countries are better off (i.e., they reach a higher indifference curve in the graph below) with than without trade. Trade is of mutual benefit. (Gut 1 and Gut 2 are the goods traded, Aa and Ab are the equilibria for both countries without trade, C is the equilibrium with trade)

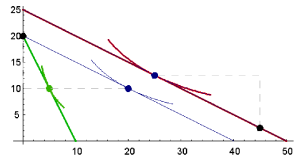

Second, he has shown that it has no meaning whether one of the countries is bigger (in the economic sense) than the other: they still are benefited or at least not worse off when they are involved in trade with each other. You can see it in the second graph. (red is the bigger country, green the smaller, blue is the situation for the smaller one with trade)

To the third argument (exploitation) my teacher answered without reference to Ricardo. He just said: “What is the alternative? Without free trade people in the poor countries would not have even these low wages they get from their multinational corporate employers.” Convincing, isn’t it?

Let’s begin with Ricardo. Without deciding whether free trade really is “bad” or not (although I am convinced that the current structure of international trade is highly unjust – but this is not the question here, not yet at least), I would argue that one cannot use Ricardo’s very simple theory to make arguments about modern free trade – whether in favor of or against it. The reason is simple: there are too many totally unrealistic assumptions. Clearly, a model must make some unrealistic assumptions – otherwise it weren’t a model. But, to be a good model, it cannot make unrealistic assumptions which have the potential to heavily influence the model’s output. Meanwhile, Ricardo’s model makes a lot of such assumptions (some of them were problematic in the 19th century already, many are because of the more complex structure of trade in the present world). First: it assumes that labour is the only productive factor. Thus it ignores the existence (and impact) of further factors of production: technology, resources, capital and so on. Second: it assumes full intersectoral mobility of labour. This would mean today that a worker from the steel industry has no problems to switch to the agricultural sector. Third: it assumes full employment of the factor labour, i.e. no such thing as structural unemployment. This is clearly a critical assumption as well. Fourth (an important assumption not mentioned in the lecture): it assumes the immobility of capital. In our world, capital is highly mobile – it is actually more mobile than labour.

You can see that there are too many critical assumptions in Ricardo’s theory to claim that it may be a reasonable foundation of an argument about today’s world. In other words: for the WTO-world of international trade Ricardo is completely worthless.

What about the “What is the alternative?”-argument? In my opinion it is even more worthless than those built upon the theory of comparative advantage. Its main deficiency: it doesn’t answer the question implied in the “antiglobalist” argument. The question is this: Can trade be good considering the fact that we (the rich) are exploiting the poor? Meanwhile, the answer is: Trade is good, because without trade people would be even poorer. This is equal to the following pair: Can it be good to beat somebody? It is good to beat somebody, because he could be killed in the first place. The problem is not trade itself, but how it is designed. By now, it is designed so as to promote exploitation of workers in poor countries. Surely, these workers would probably be worse off without their exploitative jobs. But they could be much better off if global trade structures would be redesigned. And this is what the “antiglobalist” arguments imply.

This seems to be part of our earlier arguments. Firstly, let’s forget about the “exploitation” – it is a catch all phrase. Current model of global trade is skewed in the favour of developed countries. If you look carefully it provides a lot of benefits for those with well developed and stable economies but significantly less to those which happen to be just developing. Just a simple example international travel. For the citizens of developed countries it is easy. In most cases they do not require visas and lngthy process. The same does not apply to the poorer part of the world community. If you arrive in some distant poor land you have a good chance of obtaining visa at the point of arrival ( you will have to pay a fee but it is better than being sent back or detained). The same will not apply if a tourist from a distant land arrives in EU or the USA. In a similar way the global trade/economic order is structured. Just in short.

Regards,

I used the word “exploitation” because my teacher did. With regard to the rest of your comment, I agree. That’s exactly what I meant to emphasize.

David Ricardo: Destroyers of Comparative Advantage

In Chapter 19 of the 1817 classic On the Principles of Political Economy, and Taxation, David Ricardo mentions, in addition to war, removal of capital and a new tax as destroyers of the comparative advantage which a country before possessed in manufacturing.

Deferral of tax on foreign earnings by multinationals, as long as those earnings are not returned to the U. S. results not only the loss of U.S. tax revenue but it incentivizes the remove jobs and capital, which feeds upon itself to reinforce a downward spiral for our economy.

China’s pegging its currency to the U.S. Dollar, in form this is not a tax, but in substance acts as a tax on all U.S. exports to all U.S. Trading partners, not just exports to China.

The unresponsiveness of U.S. Political leaders to these changes that David Ricardo, the father of classical political economics, warned; has subject U.S. businesses and workers to a similar plight as the frog in the boiling water parable.

“The U.S. trade deficit is a bigger threat to the domestic economy than either the federal budget deficit or consumer debt and could lead to ‘political turmoil.’ Pretty soon, I think there will be a big adjustment.” — Warren Buffett, January 2006